By Lottie Ennis

A tale as old as Hollywood itself – a youth obsessed culture that creates a cinematic invisibility of older, post-menopausal women in the industry.

Ageism in Hollywood is a pervasive problem limiting the career of many actresses. Stars such as Helen Mirren and Meryl Streep have commented many times on the outrageousness of Hollywood writers and casting directors. Indeed, on the already rare occasions where a female character is over fifty, they would often cast someone much younger for it. The unfortunate consequences of this for ageing actresses are financial inequality with their male counterparts and unemployment. However, the most insidious side effect of this ageist attitude is the invisibilization of post-menopausal women and their stories in everyday life.

A recent claim by the Guardian showed that in 2014’s twenty highest grossing films, on average three out of ten actors were women, and only eight percent of those actors were between forty and fifty-nine – with a shockingly low two percent for over sixty. Considering the average woman in the UK lives to about eighty years old, only using women in their twenties for films causes huge issues with representation by leaving out a huge proportion of an actual woman’s life. For example, in the movie Book Club (2018), both Jane Fonda and the film’s director said that there was a lot of pressure to reduce the original age of the characters to the fortys instead of following the original script which included characters who were over seventy-five. Although actresses such as Jane Fonda and Mary Steenburgen who are eighty-two and sixty-seven respectively starred in the film, the initial resistance from film executives to cast older women shows a undeniable preference to use younger women – even when the original plot says otherwise. Some producers still seem to believe that films with older women may not be as successful but films like Book Club dispute that with huge box office success.

“Older men do not face nearly the same level of discrimination”

Signs of an ageist approach to women in cinema are clear, and they are doubled with the omnipresence of sexism, as older men do not face nearly the same level of discrimination. The San Diego State University found that in films in 2017, forty-six percent of male characters were over forty versus twenty-nine percent of female characters in the same age group. Actresses are clearly at a disadvantage: there are few roles written for women over forty, and even fewer that will actually cast women this age.

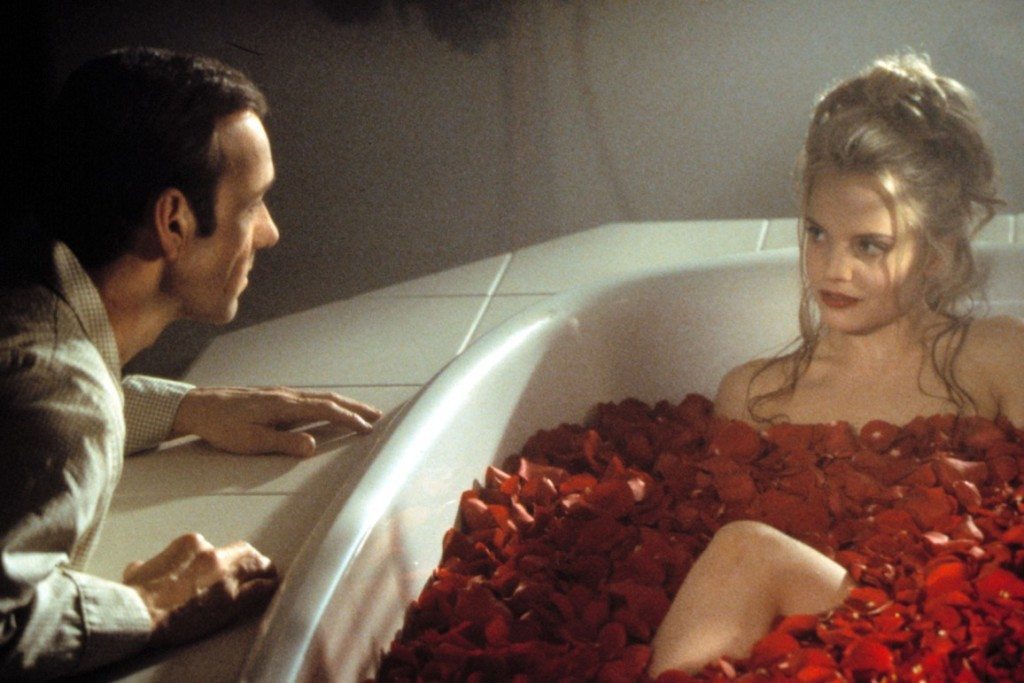

Another common phenomenon is age gap in relationships, usually between an older husband and a much younger wife. As Maggie Gyllenhal recounts, she was passed over at age thirty-seven to play the lover of a fifty-five year old man, because she was told she was too old. Clearly, age gaps happen in real life: but when a big age gap becomes the norm in films, there is more to it than just the influence of real life.

“By the time you’re twenty-eight, you’re expired”

As the film producer Stephen Follows highlights, movies are so pervasive they can have an effect on what we as an audience would deem as an appropriate age gap, and is often one of the first ways children see relationships outside of their own household. It is hence vital to have a variety of different age relationships and not just one type with an older man and much younger women. Furthermore, the lack of age matching means that male actors can continue working as they age whilst female actors can become invisible or redundant when they hit a certain age. As Zoe Saldana, has aptly summed up whilst talking about the bias in cinema; ÔÇÿby the time you’re twenty-eight you’re expired.’

“Male actors can continue working as they age whilst female actors can become invisible or redundant.”

Ultimately, limiting women to finishing their on-screen careers by the age of forty not only stops actresses to fulfill their potential, it also undermines one of the main purposes of cinema: to tell and reflect the stories of our world. If the stories of older women are not being told, it is condemning a huge part of the population. It is saying: “you don’t have a future after you hit forty.” Older women deserve light to be shed on their stories too.