By Mike O’Brien

SPOILER WARNING: This article contains major spoilers for Portal (2007), Halo: Reach (2010), Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1980), and Crime and Punishment (1866).

In powerful art, there is no such thing as stasis. Of the 205 special-effects shots in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, many frame celestial still life landscapes, ossified gazes at ossified space. For centuries, playwrights have halted time itself before our own eyes with the stage freeze. The prehistoric painters whose scores of hands line the cave walls in Altamira could never have dreamt of art in motion. Yet there is no such thing as stasis in powerful art. For in Kubrick’s perfectly still space, our eyes dart between the stars, conceiving the paradox of a lifeless void which contains all life. When the playwright pauses time, our eyes meet Macbeth’s, savouring and lamenting the eternal instant before tragedy strikes, as thane plunges dagger into king, and himself into damnation. The hands on the walls of Altamira have not moved since the paint dried 36,000 years ago, yet we cannot resist animating the amazement of our firelit ancestors sprawling in charcoal and ochre, giving birth to rampant expression. Indeed, there is no stasis in powerful art. The audience, in its pursuit for meaning and identity, animates even the most sedentary image, scouring left and right, backwards and forwards, until we detect the action of inaction. Stasis is the absence of meaningful elements: the death of scene.

Not all art is born equal. We’ve all abandoned an unworthy film in the second act and scoffed at inoffensive songs that reek of boardroom box-checking. Just as pups howl to the moon, we understand dramatic structure from birth. Consider that even the two most unstudied movie-goers can emerge from a film and say to one another, ÔÇÿI loved the scene where [ÔǪ]’. The ancient crowds of the Great Dionysia could sniff dialogue from soapboxing, which they expressed with the elegant critique of dung-slinging. Indeed, fine art sidesteps our disbelief and commands our unwavering attention. To turn the page without finishing, or to skip a scene we’ve never seen, feels utterly unthinkable, disrespectful, even. Yet, in the videogame medium, this very act is a programmed function. With the press of a button, video games allow players to terminate lines mid-speech, cutting voice actors off mid-performance and skipping time to the next line. This universal behaviour begs the question: why do gamers slice through dialogue ÔÇô even in games they love – when they would never think to do so during a film? Are games, like soulless films and hackneyed lyrics, unimaginative and disingenuous? Heavens, no. But by galloping through their dialogue, we tell the game designer: ÔÇÿYou will not surprise me.’ We skip dialogue because, the moment we finish reading a subtitle, instinct tells us we have exhausted the moment of its value. We have lost faith in the designer’s telling. The scene has grown static.

The game designer faces profound challenges and limitations unique to their form. To command its audience’s unerring attention, and the faith to digest every moment of the story’s telling, they must reimagine the principles of scene for a new medium.

The Purpose of Scene

No scene exists in a vacuum. Scene is a delicate structure in the superstructure we call story. Most stories consist of three acts, better known as ÔÇÿbeginning, middle, and end.’ Each act consists of sequences, a series of events which takes its characters from one place to another. A scene is merely one such event.

A scene is a duel, a tug of war between the protagonist’s desires and the forces of antagonism which obstruct them. In this tug of war, the rope is the value at stake, and each tug for control is known as a ÔÇÿbeat’ ÔÇô the final, microscopic unit of story which comprises all scenes. In other words, a beat is any action a character takes to advance their position. The beats escalate in intensity, shifting the value from positive to negative, until the scene climax, a moment in which the audience senses palpable, irreversible change.

All scenes, whether haunting, amusing, or touching, dramatize a conflict of values.

A Christmas Carol (1843): Ebenezer Scrooge dismisses two beggars. The beggars believe in social welfare. Scrooge believes in rational egoism.

BoJack Horseman (2017): BoJack declares that he will not eat the cookies for breakfast, and then immediately eats them. BoJack believes in a better, disciplined self. BoJack also believes in instant gratification.

Jaws (1975): a shark eats a skinny dipper. The skinny dipper believes Earth is humanity’s playground. The shark delivers a convincing seminar on natural selection.

Foremost, the scene must serve at least one of the following three functions:

- Advancing plot

- Delivering exposition

- Developing character

The very best scenes accomplish all three simultaneously through conflict, teasing us with hints and fostering an appetite for the major dramatic question. Will the jury convict the defendant? Will Walter White escape justice? Will Clarice Starling stop Buffalo Bill? Each scene from 12 Angry Men, Breaking Bad, and The Silence of the Lambs edges us closer to the truth, titillating our curiosities and perverting our loyalties.

Consider the iconic scene from The Empire Strikes Back. Rebel fighter Luke Skywalker (protagonist) and imperial lord Darth Vader (antagonist) clash in a lightsaber duel of fates. The value at stake is lifeÔǪ or so it seems. In fact, the real duel is a spiritual battle for Luke’s loyalty. Notice how each beat builds in intensity, oscillating the value at stake (loyalty) between positive and negative, ending in irreversible change.

Vader severs Luke’s hand.

Luke clings to the gantry for dear life.

Vader tells Luke that he cannot fight.

Luke declares that he will never join the Empire.

Vader, realising he cannot destroy Luke’s resolve in battle, attacks his reality: ÔÇÿyou never knew what happened to your father’.

Luke reaffirms his truth, accusing Vader of killing his father.

Vader targets Luke’s very identity, revealing that he is Luke’s father.

Luke screams in defiance.

Vader implores Luke to accept the truth and rule together as father and son.

Letting go of the gantry, Luke chooses death.

In just ten beats, screenwriter George Lucas transforms the conflict from Lord vs Revolutionary to Father vs Son, a duel for life, death, family, and loyalty, where each combatant wins and loses simultaneously. Lucas’ scene advances plot with conflict, build in intensity, delivers critical exposition, develops character, and dangles the fate of Star Wars‘ major dramatic question before us: will Luke Skywalker defeat Darth Vader?

Players vs Viewers

The videogame industry’s finest writers know the anatomy and objectives of scene. The greatest issue they face is the mountain of complications distinguishing the player from the viewer. Viewers flock to the cinema for a filmmaker’s guided tour of a vision. They control what we see, what we hear, from which angle, and how long we linger. The player is an altogether different beast. Should you attempt to hold a player’s hand, expect them to spit in it. The player craves agency above all else, for their medium celebrates the unique dimension of interactivity. Much to the terror of the game designer, the player demands from them the same meaningful experience films deliver, but demands control of perspective and action. What tools remain for the game designer, and what tools must be invented?

The Cutscene

In other mediums, the audience identifies scenes with ease. We know the theatre’s dimmed lights and drawn curtains concludes the scene. The filmmaker wields full control of the timeline, combining transition and juxtaposition to stage new conflicts. In videogames, only one such conventional form of scene exists: the cutscene.

Upon triggering certain conditions ÔÇô such as completing a mission or reaching a destination – the player loses full control over their character and the camera. From there, the game designer stages a conventional ÔÇÿscene’ akin to film, with fixed camera shots depicting beats and elements in the scene.

In moderation, this technique imbues rare moments with cinematic grandeur. Depending on the game’s usual camera perspective, the cutscene may be a necessary departure to convey story elements. But the designer must implement the cutscene with extreme caution. The cutscene denies players not only the agency they crave from games, but the freedom to explore and experience scenes from their perspective. Indeed, the cutscene does not offer a scene which embraces the interactive spirit of the video game medium. It tells a linear scene in spite of it.

Missions and Objectives

Most games consist of missions. Depending on duration, missions share a similar structure to either the ÔÇÿscene’ or the ÔÇÿepisode’. Missions deliver clear objectives to the player which imply criteria for victory (rescue the princess) and failure (die in a hole). This is not unlike the scene, which sees two entities wrestle between positive and negative charges of a value. And, just like with scene, anyone who has touched a controller can sense the difference between a well-written mission and a stocking filler.

Main missions must advance or complicate the major dramatic question of the central plot. If they fail to do so, we groan, roll our eyes, and prepare for busywork. In Assassin’s Creed Valhalla (2020), Viking siblings Eivor and Sigurd lead the invasion of Anglo-Saxon England. In the first mission, a witch prophesises that Eivor will betray Sigurd, birthing the major dramatic question: will Eivor betray Sigurd? After thirty hours of main missions, not even one brings us closer to the truth. Instead, we meet bland characters whom we will never see again, whose loyalty we must nonetheless earn by running errands. To emphasize how wasteful achieving nothing with that time is, thirty hours covers the entirety of BoJack Horseman. Good grief.

Portal (2007) puts the player in a research facility where an Alexa-esque robotic voice encourages us to solve physics puzzles creatively. Each mission takes place in a new test chamber, escalating the complexity and danger of the puzzles. That is, until the encouraging voice instructs us to walk into an incinerator. By instructing us to die, Portal breaches our trust, shifting our mission from ÔÇÿcomplete novelty puzzles’ to ÔÇÿescape this nightmare’. Using only physics puzzles and a disconcerting voice, each mission in Portal advances the plot, innovates the gameplay, and intensifies its simple premise with amusingly sinister forces of antagonism. This timeless masterpiece never wastes a moment.

Sci-fi shooter Halo: Reach (2010) uses mission objectives as a narrative device. The game follows Noble Team, a group of elite supersoldiers at the epicentre of an alien invasion. The game begins with an image of our character’s helmet, its visor cracked, laying in a desolate field. Immediately, our major dramatic question surfaces: will we survive? In each mission, the alien threat intensifies, forcing the squad into horrifying situations which unceremoniously kill our comrades one by one. The final mission, ÔÇÿLone Wolf’, leaves us alone in a desolate field, Covenant brutes stampeding our way, as the game hands us our simplest objective yet: SURVIVE. By handing us an objective we’re destined to fail, the game entrenches us with the final duty of a forlorn soldier, a gutwrenching twist of the dagger.

The mere delivery of mission objectives can even define the experience. In most games, mission objectives manifest on the screen via a head-up display (HUD). In the pause menu, the player can also access a ÔÇÿjournal’ or ÔÇÿmission log’ which tidily organises each available mission and allows them to choose which to pin on the HUD. Dark fantasy-action game Dark Souls (2011) throws the player, a lowly husk cursed with eternal life, into a miserable world of feral beasts and sunken knights who wander eternally like clockwork. Rather than obeying fantasy tropes, which venerate the hero as a special individual destined for greatness, Dark Souls demeans us as weak, lost, and insignificant. Indeed, Dark Souls never uses a HUD to remind players of what they must do, because to pin an objective on-screen is an almost motivational act of direction, convincing us of its possibility. Instead, Dark Souls offers zero objectives and no HUD, populating its world with morbidly curious hints instead. In one instance, a crestfallen warrior mocks our persistence, but humours us with a hint: ÔÇÿThere are two Bells of Awakening [ÔǪ] Ring them both, and something happensÔǪ’. With its cryptically minimal hints in lieu of objectives, Dark Souls both belittles the player’s place in the world whilst respecting their curiosity.

Side missions may connect to the central plot but will not advance it. Because they face no obligation to advance the central plot, side missions can tell independently contained stories with their own major dramatic questions. The side mission’s closest relatives in other mediums would be the anthology episode or bottle episode: examples include ÔÇÿRixty Minutes’ (Rick and Morty), ÔÇÿFly’ (Breaking Bad), and ÔÇÿFish Out of Water’ (BoJack Horseman).

Because side missions are alternative by nature, the most memorable and impactful side missions play with the main mission formula to deliver something else. In Ancient Greek action game Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey (2018), the structure for its main missions is:

- The player speaks to the mission giver

- The player enters an epic combat scenario

- The player reports victory/defeat to the mission giver

In the side mission ÔÇÿThe Grand Minotaur’, we encounter a cheeky street urchin who invites us on a tour to see the region’s legendary Minotaur. The dramatic question: is the Minotaur real? If we accept, our objective becomes: ÔÇÿfollow the boy’. A comically long and farcical tour ensues as the boy points to rocks and claims they are Minotaur droppings. At the end of the tour, he leads us to a cave, where a man in a minotaur mask whimpers, ÔÇÿI am the Minotaur. Roar.’ The boy then casually charges an absurdly high tour fee. Outraged, we decline, and the Minotaur man attacks us. After we survive the world’s worst robbery, the boy emerges and offers us a 10% discount on merchandise.

ÔÇÿThe Grand Minotaur’ offers a brilliant foil to its main missions. Though it closely mirrors the main mission structure, it builds a scene with so many comically uninspiring objectives and harmless beats that the eventual combat scenario becomes an unexpected punchline rather than a gratuitous moment.

World as a Canvas for Scene

Games may share the screen with film, but unlike stitching frames in sequence to produce a video, games use graphics engines to render a realtime environment. Film uses perspective and detail to conjure the illusion of space. Games, meanwhile, simulate space. When game designers populate these spaces with reactive elements, dynamic events and behaviours produce scenes. Because games react to the player, their worlds and denizens must be taught how to respond to action and presence. Thus, game designers have access to a dynamic form of scripting: rules of logic. In Rockstar Games’ Grand Theft Auto V (2013), an open-world action game set in a fictionalised Los Angeles, the player can switch between three main characters at any point, one of whom is Franklin, a black man. Whilst playing as Franklin, white pedestrians avoid the player in the street, whilst police officers harass them unprovoked. By forcing the player to play by different rules depending on their character’s ethnicity, scenes emerge which metaphorize the different rules people of colour live by in modern America.

ÔÇÿThe oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown,’ wrote novelist H.P. Lovecraft. Perhaps no game respects this principle quite like the original Half-Life (1998). In Half-Life, we play as scientist Gordon Freeman who, after a botched experiment, opens a rift in the space-time continuum through which alien life floods into the facility. Half-Life virtually never takes camera control away from the player, offering full freedom of perspective. Ironically, unabated vision can leave us blind, a truth that Half-Life devilishly exploits. As we clamber for escape from Black Mesa Headquarters, a dizzying array of events constantly surrounds us. We sprint through corridors, whilst scientists bang on windows, screaming for help. A gunshot down the hall steals a glance from us. By the time we turn back to the window, nothing remains but legs dangling from the ceiling. By respecting player perspective and disorienting us with a 360-degree scene, Half-Life empowers the beats of its scenes by allowing us to miss them, forcing us to imagine the worst.

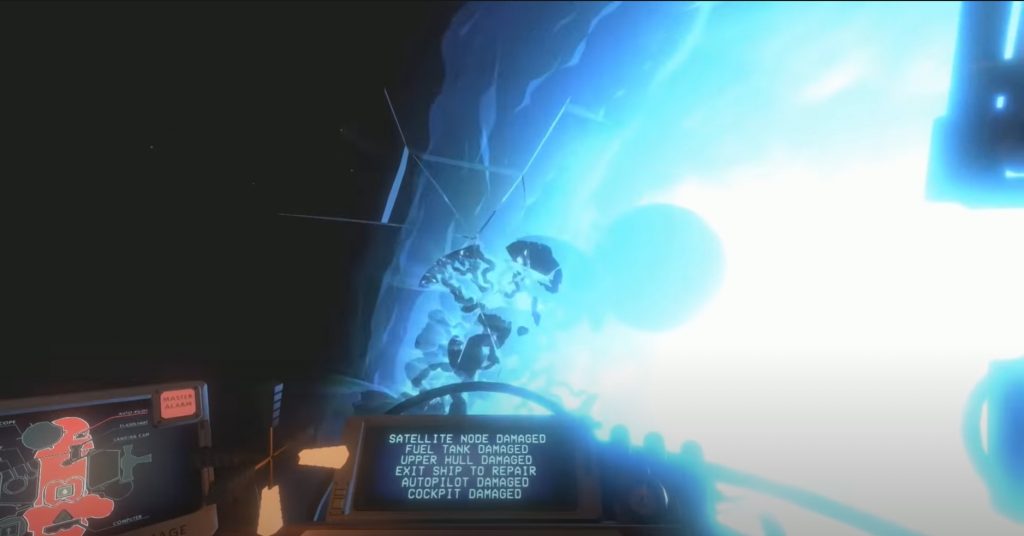

Masterful designers can build an entire story around the concept of exploring space without explicit direction. Sci-fi mystery game Outer Wilds hands the player a spaceship and an oxygen tank, setting them loose in a merciless solar system of planets, comets, black holes, asteroid fields, and quantum moons. No matter what they do or where they choose to go, after 22 minutes, the sun erupts into a supernova, incinerating everything in the solar system. The moment the all-encompassing blue flame consumes us, visions of our journey flash by in an instant. We wake up precisely where we began. The truth dawns on us: we’re in a time loop.

22 minutes is nowhere near enough time to solve the mystery of Outer Wilds’ solar system. But it is just enough time to reach the source of a strange distant signal, or crash-land on an abandoned alien structure. With no map to guide us, no voices telling us where to go, and the sands of time filling our lungs, we intuitively know what we must do with our 22 minutes: discover. Each life in Outer Wilds becomes a 22-minute scene between you and the forces of time and space, daring us to delve into its darkest nooks and make a single discovery. We may die a dozen times just to find a memo etched on a cave wall by a long-dead scientist from an alien race. But once we find it, we dare not skim-read the dialogue. Instead, we cling to it, digesting and wrestling with every word to find rhyme or reason before the inevitable supernova pulls us away. Because we can find any clue in any order, every piece of evidence mutates in meaning with each new discovery, as new combinations of information bloom new possibilities, new conclusions, and new answers to the major dramatic question: can we defeat time?

When the game designer takes the camera from their players, they often fear the audience will otherwise miss something. But the games industry’s innovators do not shackle the videogame to the scenic norms of film. Outer Wilds never seizes the camera, never drags us through the beaten path. Rather, it builds a living world which resists and rewards our will. By populating environments with clues that connect to a central mystery, audience-savvy designers tap into an important principle: curiosity makes detectives of the audience, not flashy camerawork.

Conflict

Even the most patient players race through dialogue when they emotionally disconnect from the scene. But what lies at the heart of this severance? Almost every time, the answer is an absence of compelling conflict.

One must not mistake conflict with violence or action. Conflict equals desire versus resistance. In Dostoevsky’s 1866 novel Crime and Punishment, the poverty-stricken rationalist Rodion Raskolnikov bludgeons a pawnbroking pensioner and her dim-witted niece to test a thesis. After the act, he spends upwards of five-hundred pages staring at the pavement and mumbling to himself about Napoleon. Every page drips with conflict. The murder cleaves Raskolnikov’s consciousness in two: the idealogue, who rationalises victory, and the empath, who scorns inhumanity. Between the cracks of his mundane musings, we sense that this guilt-ridden intellectual craves the only thing a paranoid murderer can never experience again: peace of mind.

In The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, players explore a gritty Nordic fantasy world caught in the crossfire of a civil war and the resurrection of world-devouring dragons. Along the way, our character can speak with almost everyone in the world, from rural serfs to wealthy jarls. This ambitious idea results in dreadful scenes. Our character stumbles upon an agrarian village in the tundra. We spot a farmer tilling the frozen soil, the threat of dragons and conscription looming over his humble life. We approach him, a stranger in a cautious land, and say, ÔÇÿtell me about this village’. Abandoning his duties immediately, he delivers a concise, eloquent, and comprehensive overview of the village, its recent history, and its prosperity. We respond: ÔÇÿFarewell’.

With no characterisation, dull exposition, and no conflict, we cannot call this pseudo-conversation a scene. We see this conversation hundreds of times across dozens of open-world games which allow us to interact with any person we see. Rarely do we remember or care for any of them, for we know they are no more human beings than exposition in man’s clothing.

Alternatively, in medieval fantasy The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, we play as Geralt, a mutated human who makes a living as a monster hunter-for-hire. As a mutant, Geralt faces widespread distrust and ostracism from human communities. When Geralt approaches a farmer in The Witcher 3, the farmer declines to offer us a comprehensive history of the land. Instead, before we can get a word in, the farmer mumbles: ÔÇÿfuck off, cat eyes’. In just four words, this farmer creates conflict, teaches us the prejudice of his land, and gives us something to remember.

Action, Resistance, and Character

Crime and Punishment succeeds because Raskolnikov faces both internal and external resistance which complicate one another. External forces of poverty and familial suffering compel him to steal and murder. Internal forces of ideology and grief exile him to madness.

When we disconnect emotionally from conflict in games, it is often because the forces of resistance are entirely external. In a multiplayer shooter game where thrilling chaos is the sole purpose, enemy gunfire suffices. But if a shooter game hopes to tell a story, that gunfire must either stir something within the heart of our character or reveal a truth about him. Such is the purpose of conflict in scene.

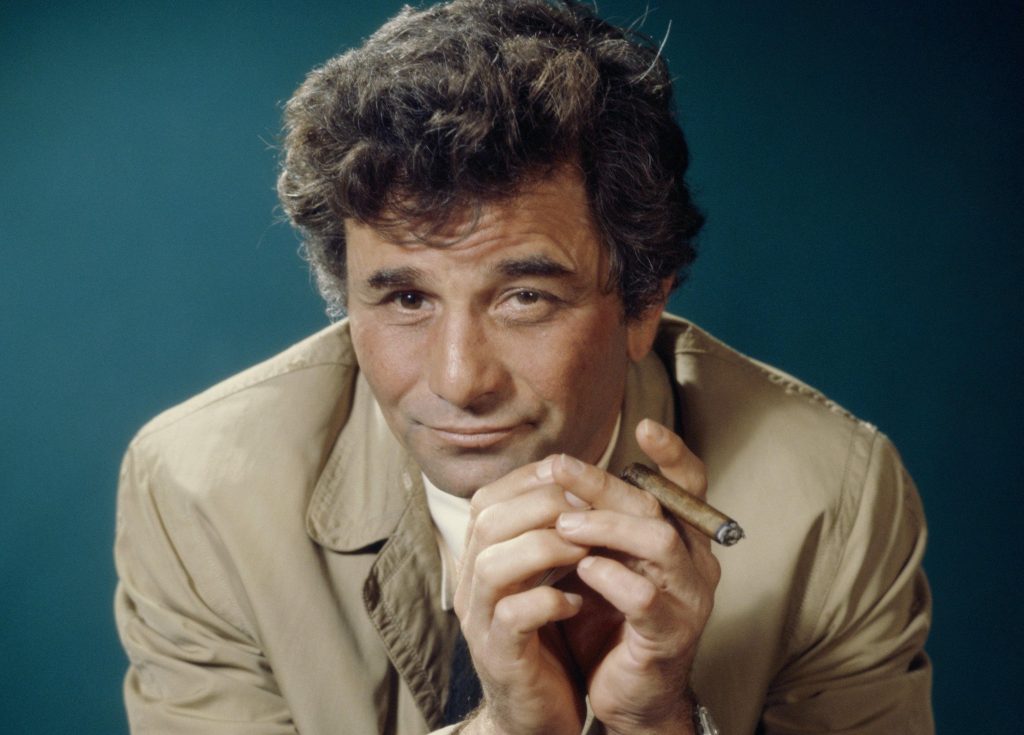

If the formula for conflict is Desire vs Resistance, the formula for character is Action vs Resistance. In real life, we are what we do. Fiction is no different. No matter what he insists to himself or others, a character is what he does in the face of resistance. Detective Columbo (from Columbo) and Jotaro Kujo (from JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure) are crude, trenchcoated, chain-smoking masters of perception and deception who outsmart murderers with calm and calculated confidence. In each episode of their respective shows, they imply suspicion to put their opponents on the backfoot. Then they feign ignorance and weakness to lull their opponents into a false sense of security, whereby the killer’s hubris exposes a critical flaw. They even pursue the same value at stake: justice. But the critical difference in their character is the action they take to exact justice. It is absurd to imagine Jotaro Kujo pulling back the curtain to reveal a hidden police squad primed for a sting operation. Stranger yet is the thought of Detective Columbo screaming as a six-packed phantom of his creation thunder-punches the suspect straight to hell. Jotaro wields magic fists. Columbo never carries a gun. That is who they are.

Game designers struggle to convincingly characterise their protagonists because they neglect the definitive properties of action. Action-adventure shooter game Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End (2016) follows retired treasure hunter Nathan Drake as he embarks on one last adventure to save his brother and find a legendary treasure. In doing so, he endangers his marriage, as his wife craves a stable life devoid of gallivanting and gunfire. Drake embodies the adventure hero archetype. He’s charming, cares about his family, and he values the history of treasure over wealth and fortune. A problem arises, however, when Uncharted 4 shines a spotlight on Drake’s moral compass. In cutscenes, Drake often implores diplomacy, allowing villains to escape in the name of mercy, and laments violence. Unfortunately for Drake, as the protagonist of an action-adventure shooter game, he slaughters hundreds of human enemies, wisecracking at their deaths. The story spirals into cognitive dissonance. Uncharted 4 insists upon Drake as a do-gooder doing derring-do, whilst refusing to acknowledge the blood we spill with his hands. Every scene climax depends on Drake’s morality, yet scene after scene consists of dozens of violent beats. Adding insult to injury, Uncharted 4 encourages us to tut-tut at Drake for betraying his wife’s trust, whilst nudging us turn a blind eye as he frolics in the fields of genocide. Uncharted 4 attempts a moral story in isolation of its immoral action, and as we know, action is character.

The very best games embrace the central action of their genre and build a character around it. Celeste, for instance, is a platforming game about climbing a mountain. How did studio Matt Makes Games build a story around this? They put us in Madeline’s shoes, a transwoman who ventures to climb Celeste Mountain to reclaim herself from the stasis of anxiety and uncertainty. This delightfully human premise marries game design and scene perfectly. Just as beats must escalate in intensity to the scene climax, the terrain in a platformer must escalate in complexity to incrementally challenge the player. In Celeste, not only does Madeline’s anxiety grow fiercer with the terrain; her anxiety itself becomes an obstacle for the player. Indeed, when Madeline’s anxiety overwhelms her, her inner demon (Badeline) escapes her mind and physically chases us through levels. Both Madeline and the player face the same forces of resistance with the same determination. As we fall from the mountain time after time, we must breathe and try again. To finish Celeste, both Madeline and the player must learn the same lesson: only when our resolve conquers our anxiety can we reach the top of the mountain. A woman is what she does. Madeline climbs.

In Closing

Perhaps more than any other creatives, the games industry’s storytellers deserve our sympathies. They cannot write a two-hour movie script and spread it convincingly across a fifty hour experience, yet they are often made to do so by the suits upstairs. They must tell a story with a fraction of the tools and control wielded by playwrights and filmmakers, all whilst contending with an audience who loathes intrusive guidance. Most studios develop games with the gameplay loop in mind. Each level or section in a game is in fact an arena in disguise, a playground built to encourage us to jump creatively, shoot tactically, and drive recklessly. To wrap a compelling story around these playgrounds takes impeccable craftsmanship and vision. Consider also that the brutal pragmatism of project management and the industry’s horrendous working conditions do little to foster or empower creative storytellers.

Rather than emulate the techniques of the playwright or the screenwriter, gaming’s storytellers should pursue symmetry between scene structure and game design. The scene demands that a conflict of escalating beats between protagonist and forces of resistance will reveal character and advance the plot. The game demands that players face escalating challenges to prove skill. The capacity of the game designer to harmonise these formulas determines the game’s meaning and impact. Ultimately, whatever the player does, and whatever the player faces, must metaphorize the human struggle of their character. All the player really does in Celeste is climb obstacle courses. It only means something to us because, by proving our skill, we prove Madeline can reclaim herself from mental illness.

Moreover, the game must embrace player agency, not seize it. Only an unconfident game designer relies on frequent cutscenes to force focus. The game designer should aspire to build worlds and environments which inspire curiosity, allowing players to lead scenes with investigation and action, rather than snatching their controller and force-feeding them linear exposition. Gamers shred through dialogue because dialogue by itself is not scene. Too much of it is conflict-averse babble that we skim-read for detail because we know there is no subtext, no humanity behind it.

The most profound games are often the quietest. Throughout Outer Wilds, we witness the supernova devour the solar system every 22 minutes. Yet with each new discovery we make, we ascribe this wall of flame with new meaning. It is a thing of beauty, a thing of horror, a testament to our cosmic insignificance, a testament to our limitless determination. Even now, I see something different every time it arrives. Such is the genius of Kubrick, Shakespeare, and our ancestors in the Caves of Altamira. We animate the inanimate with meaning after meaning. Only when the artist fails to construct true scene does the audience experience true stasis.