By Mike O’Brien

Netflix sensation Black Mirror is Charlie Brooker’s occasionally brilliant exploration of human conflict through the lens of future technology. But could these technologies ever truly exist? And if so, are the scenarios likely to occur? I’ve painstakingly analysed every single episode of the show and assessed each one’s prophetic vision, rating them out of 10 based on their social and technological foresight.

It should go without saying that this article contains massive spoilers for all episodes of Black Mirror.

The National Anthem (2011) ÔÇô 1/10

Black Mirror‘s pilot episode sees a publicly adored princess kidnapped by an unknown assailant, who then threatens to murder her unless Prime Minister Michael Callow has sex with a pig on live television. The National Anthem doesn’t feature any future technologies; instead, it uses digital manipulation software and the internet to make a statement about the pervasion and voyeurism of our current media ecosystem.

Since The National Anthem is rooted entirely in the present, it can’t be considered technologically prophetic, save for its use of deepfakes which are a much greater point of discussion now than in┬á2011. It did however feature a prime minister embroiled in a public pig sex scandal, which actual Prime Minister David Cameron allegedly indulged for his initiation to the Piers Gaveston Society. Bonus points for calling Piggate, but only one since the whole affair is unverified. Beyond that, it’s deeply unlikely that the government would give into terrorist demands.

Fifteen Million Merits (2011) ÔÇô 7/10

Fifteen Million Merits is possibly the most dystopian episode of the entire series. It depicts a world wherein citizens cycle on an exercise bike to produce electricity for the unknown powers at be, earning ÔÇÿmerits’ that can be spent on various media to distract them from their bleak existence. It’s a hyperreal, depressing-as-hell metaphor for the mindless 9-to-5 grind and the mediatized environment we tune into to tune out of life.

Though it depicts a surreal world of absurdly aggressive media saturation, the episode did predict several real-world developments. In the world of Fifteen Million Merits, advertisements are in constant view on almost every observable surface, both inside and outside of the home. A number of major cities such as London, Sao Paulo, Tokyo, Tehran, New York, and Paris have plastered massive digital advertisements on everything from escalators to buildings to the bloody sky. At one point in the episode, the protagonist, Bing, looks away from an advertisement, which pauses upon detecting his averted gaze. Two years after the episode aired, Amscreen announced that it had developed advertising technology capable of discerning whether people were looking in realtime. A similar concept to riding an exercise bike for rewards surfaced also in Brazil; in a Santa Rita do Sapucai prison, inmates ride exercise bikes to generate electricity for the state in exchange for shorter sentences.

Though less of a prophecy and more of an observation, Fifteen Million Merits’ most astute criticism is that The X Factor is worthless, exploitative rubbish.

The Entire History of You (2011) ÔÇô 8/10

The Entire History of You asks the question: what if we had a digital memory of everything we ever saw? The episode’s answer is a plot of infidelity and obsession which argues that paranoia and insecurity would toxify your relationships even more than they already do. The technology in question is called a ÔÇÿgrain’ in the Black Mirror universe, a device which records everything you’ve ever seen and provides instant playback through either your eyes or on a TV screen. This technology is by no means out of reach; only a few years after the episode aired, smart contact lenses, which can record anything you’ve seen and play it back, began development at Sony.

The real obstacle between the ÔÇÿgrain’ and reality is storage space; whilst Samsung are working on a similar contact lens that transmits images to external storage, the amount of storage space needed to record your entire life and play back any moment of it at will would be absolutely monstrous. An episode of Black Mirror ÔÇô which typically lasts around an hour ÔÇô takes up 1.34 gigabytes at a resolution of 1080p. If the grain records life in full-HD, which is a very lenient goalpost for the distant future, every day would take up about 32 gigabytes of space. Since we know the grain is implanted at a very young age, the storage space consumed by a 25-year-old would be almost 295,000 gigabytes ÔÇô and that’s for a single person. The technology is certainly getting there, but affordable storage has a long way to go.

Be Right Back (2013) ÔÇô 4/10

In Be Right Back, a young woman named Martha loses her boyfriend, Ash, to a car accident. Instead of grieving healthily, she consults a program which draws on all of Ash’s past social media activity and online messages to create a communicable AI that simulates his behaviour. What’s more, the experimental final stage of this service provides an android that moulds itself into Ash’s exact physical form, which she inevitably ends up knobbing.

Horrifyingly, Ash’s android form is not entirely beyond achievement. Academics from Waseda University and manufacturers from NTT Docomo have created a shape-shifting android which can change its face. If a 3D scanner is used on a person, the android ÔÇô named WD-2 ÔÇô can manipulate any of its 17 key facial points to replicate their face, including their hair and skin colour. It’s far off the technology we see in Be Right Back, but certainly not the impossible vision you might have reasonably assumed it was. However, this technology dates back to the mid-2000s, so Black Mirror gets no prophecy points for that.

But enough about terrifying shapeshifting androids. Let’s get to the real question everyone wants to know: how realistic is its sexual behaviour? When Martha has sex with android Ash, it has no data to draw from, and therefore fails to create an authentic reflection of his sexual performance. Instead, she needs to vocalise her preferences to the android, who switches it up to implement them. Remarkably, in 2017, Realbotix CEO Matt McMullen unveiled Harmony, a sex doll capable of holding conversations, retaining important information, and learning user preferences. It’s also capable of expressing a range of different emotions, and even remembers the names of your siblings (which you would hope doesn’t come up often in conversations with a sex robot). Whilst the sex robot market is evolving at an impressive pace, Be Right Back loses technological prophecy points on account of the stagnant market of male sex robots which, in fairness, are much harder to produce given the traditionally more active role of men in intercourse. Simply put, if Martha’s shagdroid of her dead lover reflected the current limitations of male sex robots, she’d be doing all the work.

White Bear (2013) ÔÇô 0/10

In White Bear, child abductor and murderer Victoria Skillane is drugged and robbed of her memory every day, forcing her through the world’s worst Groundhog Day ever to provide justice porn for bloodthirsty onlookers.

Technologically, White Bear’s central gimmick is the use of electrodes to erase memories. This does exist to some extent; retrograde amnesia can be induced through electroconvulsive therapy, which can permanently erase memories from recent days (and even weeks in some patients). Moreover, memory loss is more severe in patients who receive electroconvulsive therapy regularly, which does lend credence to the episode. But electroconvulsive therapy’s sole use is to treat mental disorders, and its side effects were understood long before the episode aired in 2013.

On the social side of things, White Bear is a commentary on the ruthless demand for blood and suffering as ÔÇÿjustice’ within Britons, something galvanised by tabloid media. The debate on the dehumanisation of criminals, particularly those who’ve committed unforgivable crimes like infanticide, has been around for decades; discussions scrutinising the relentlessly brutal public opinion towards child murderer Myra Hindley have been around since the 90s at the earliest.

A good episode, but not a prophetic one.

The Waldo Moment (2013) ÔÇô 8/10

Ah, The Waldo Moment. In this episode, a comedian stands for parliament as a blue cartoon bear named Waldo. Making no reference to policy whatsoever, he instead wins a significant portion of the public vote by wisecracking and roasting the other candidates. GamesRadar called it ÔÇÿtotally unconvincing’. The A.V. Club called it ÔÇÿludicrous’. Far and wide, 2013’s critics lambasted The Waldo Moment for its unbelievable premise; surely democracy could never be corrupted by the personalisation of politics and populist rhetoric?

Your mind may naturally gravitate towards recent political upsets, but bizarrely, a situation almost exactly like this occurred in 2003. Stuart Drummond, best known as H’Angus the Monkey, the official mascot of English football team Hartlepool United, stood for mayor as the mascot. Despite his lack of formal campaigning, and his only policy being the promise of free bananas for schoolchildren, he was elected for three consecutive terms as the mayor of Hartlepool.

In none of these terms did Drummond provide free bananas for schoolchildren.

White Christmas (2014) (1/10)

White Christmas centres around the technology of the ÔÇÿcookie’, a device through which one’s consciousness can be uploaded digitally and then interacted with. In the episode, the cookie assumes two forms ÔÇô one as a personal home assistant akin to the Google Home or Amazon Echo devices, and the second as a clone of a criminal’s consciousness as part of an unwitting interrogation.

White Christmas is one of many, many stories about the sentience of AI and the ethical quandary of whether developed AI should be considered a human entity. Whether this degree of technological sophistication is possible is up for debate. At present, the concepts of digital immortality and mind uploading are entirely theoretical and in the primordial stages of development. In Russia, Dmitry Itskov leads a non-profit organisation, The 2045 Initiative, whose goal is ÔÇÿto create technologies enabling the transfer of an individual’s personality to a more advanced non-biological carrier, and extending life, including to the point of immortality’. Itskov has outlined a roadmap for achieving cybernetic immortality, but its legitimacy is disputed.

The ethics of such technology are not fully developed either; for instance, if one’s consciousness is uploaded to a machine, what if the machine is the legal possession of another individual? White Christmas depicts a world which prioritises ownership over the sovereignty of the mind, but if artificial intelligence reached the emotional sentience and sapience demonstrated by cookies, it seems extraordinarily unlikely that their treatment by the state would be officially authorised in a democratic country.

White Christmas also explores the concept of virtually ÔÇÿblocking’ others in real life, rendering them unable to verbally or visually communicate with the blocker even within physical proximity. The degree of sensory manipulation required to achieve this is not within discernible reach by modern standards. That said, with a device like the aforementioned smart contact lenses, it seems potentially feasible that these lenses could interact with and identify one another at some point. To that end, assigning visual tags to other users via augmented reality isn’t difficult to imagine, but blocking others to the extent seen in White Christmas is the sort of thing you’d probably only see facilitated by an authoritarian state.

White Christmas exercises some creative license to turn the real-life concept of blocking one another on social media into a more dramatic plot device. However, much like the concept of digital immortality and the treatment of sentient consciousnesses, it is difficult to realise a world in which almost any the events within the episode’s script are a technological or ethical possibility.

Nosedive (2016) ÔÇô 10/10

In Nosedive, your eligibility for everything from loans to jobs to neighbourhoods you can live in is determined by your social credit score, an average based on how others rate their interactions with you. There are comparable systems in the West already ÔÇô Uber drivers and passengers rate one another’s conduct, and financers scrutinise your credit score before offering loans. But elsewhere in the world, Nosedive’s dystopian social media system is alarmingly close to reality.

In China, a series of social credit systems are in active development, some of which have already been deployed at both a private and state level. This score can be influenced by a multitude of factors from paying bills to behaviour on public transport. Moreover, fully deployed reputation systems like Sesame Credit offer shocking privileges based on social credit, such as registering your children to exclusive schools or even skipping hospital queues.

Two of the privileges which main character Lacie is denied throughout the episode on account of her inadequate social credit score are flight tickets and renting a car without a deposit; both are now dictated by social credit score in China.

Reputation systems and social credit apps do exist in the West, such as Peeple, but they are far less prevalent and intrusive.

Playtest (2016) ÔÇô 2/10

In Playtest, a young drifter, Cooper, takes a one-off playtesting role for a state-of-the-art horror VR game, developed by someone who is definitely not Hideo Kojima. The game connects directly to the player’s mind, drawing on their own specific fears to generate a tailored and unique horror experience to them. At the end of the episode, Cooper’s mum rings him in the middle of the test, interfering with the signal between his game and the mind and somehow killing him in the process.

Suffice to say, this sort of game does not exist in real life, but meaningful attempts to connect the game and the mind have been around for a while. In 2007, San Francisco studio Emotiv Systems developed electro-encephalograph equipment capable of receiving electric signals from the brain as inputs, the same way pressing a button would. This technology remains in its infancy to this day, and it seems unlikely that it will ever reach the extent of Playtest ÔÇô especially the potential to fry your brain to death.

However, horror games which attempt to tailor the experience to the player have been developed in the past. At the start of Silent Hill: Shattered Memories, players must take a psychological profiling test, the results of which determine various elements of the game. Alternatively, the horror game Nevermind supports the use of biometric devices, tracking the player’s pulse and adjusting the difficulty based on their stress level.

Shut Up and Dance (2016) – (0/10)

In Shut Up and Dance, a young man named Kenny is blackmailed by an online troll who infects his PC with malware and threatens to release sexually explicit footage of him to his friends and family. Like The National Anthem, this episode focuses on the horrific potential of current technology, so it’s not trying to give us a glimpse of the future at all.

San Junipero (2016) – (1/10)

In San Junipero, people on their deathbed are offered a chance to transfer their consciousness to the eponymous virtual utopia. Since it relies on the same concepts of digital immortality and the transferal of consciousness as White Christmas, there’s not much to say about San Junipero other than it will probably never happen.

Don’t worry, though. If you think about it, San Junipero’s ending is horribly depressing. Critics and viewers alike seem to think that Yorkie and Kelly driving into the sunset together is a happy ending. But the depression, loneliness, and purposelessness Yorkie finds in the BDSM club Quagmire is the truest testament of all; humans are simply not built for permanence, and her love is headed for the same aimless fate. Hooray for death!

Men Against Fire (2016) ÔÇô 0/10

In Men Against Fire, soldiers are shielded from the horrors of warfare and genocide by a neural implant. The implant, called MASS, alters the user’s perception of reality, warping civilians into garish creatures called roaches.

Neural implants do exist, and whilst their primary use is to facilitate sensory substitution for blind and deaf patients, they are also the subject of constant research by the military. DARPA is a key innovator, but their efforts thus far have been limited to animal testing; an early example includes neural implants in sharks to control their movement and gather intel on enemy naval units. Since then, their efforts to utilize animals in warfare have been curious indeed, using neural implants to turn rats and locusts into bomb detectors.

However, their use within soldiers has been limited to aid purposes, and the technology seen in Men Against Fire is not only in the very distant future, it would also be universally condemned by ethical authorities worldwide for its catastrophic potential to violate the Fourth Geneva Convention.

Hated in the Nation (2016) ÔÇô 2/10

In Hated in the Nation, a decline in the bee population leads to the innovative invention of bee-sized drones capable of pollination. Eventually, someone hacks into the bee drones and makes them burrow into the ears of people targeted by social media, causing such horrific pain that the victims slit their own throats to make it stop.

Just a year after Hated in the Nation aired, industrial design major Anna Haldewang from the Savannah College of Art and Design unveiled her prototype for a bee drone capable of pollination. It sounds like Hated in the Nation, but the drone is significantly larger than (and by design does not resemble) actual bees.

No drone akin to the episode’s killer bees exists, but the military is investing in nano-drone technology. So far, their smallest drone is the Black Hornet Personal Reconnaissance System, which looks a little like the tiny RC helicopter used to drop off explosives in Vice City’s Demolition Man, the worst mission in video game history. Insofar as commercial drones are concerned, the smallest one is the SKEYE Nano 2, which is still 1.6 inches wide (much wider than a bee). It’s certainly not small enough to crawl into someone’s ear or get into the eye, and even if it was, no drone capable of manoeuvring the human body via remote control from extreme distance is even close to existing at present.

Situationally, the notion that Twitter would allow users to elect the next victim with hashtags is absurd and would never happen.

USS Callister (2017) ÔÇô 2/10

In USS Callister, weirdo Robert Daly collects his colleagues’ DNA from lollipops and stray hairs, using it to generate digital clones. These clones serve as characters for his crew in a Star Trek-esque video game, who he abuses by wielding his control over the game to abuse them, suffocate them, and even remove their genitals.

There are claims that predictive facial construction technologies can produce an accurate render of one’s face based on DNA, but the results are not promising. When the New York Times tested it, nobody of the fifty employees there could recognise a render of reporter John Markoff. The idea of using DNA to create not only full-body clones with 100% accuracy but corresponding identities and memories as well, then, is just absurd.

Moreover, even if this technology did exist, it would never find itself within the context of any video game. A raging ethical debate exists in the present concerning the police’s forensic use of DNA to profile suspects, with some claiming it violates fourth amendment rights (to forbid unreasonable searches). Video games aren’t about to get a pass.

That said, technologies to transfer one’s likeness into video games are in active development. Universally beloved social media company and friend of democracy, Facebook, is presently working on a project called Vid2Game. Internal AI researchers claim that, from just a few minutes of footage of someone playing tennis, they can transfer that data into a playable character model. Make no mistake ÔÇô customization options in games will only get more sophisticated, and most people will naturally gravitate towards avatars which resemble them. Games like NBA 2K19 already allow you to scan your face to generate an avatar, so who knows? Just film your colleagues playing tennis under very controlled conditions for a few minutes, scan their face, and never explain your intentions. You’ll have your own NBA Callister in no time.

Arkangel (2017) ÔÇô 0/10

Arkangel is a story about an obsessive mother who embeds her daughter with a neural implant that feeds her daughter’s vision, hearing, and location to a tablet device. Moreover, the tablet allows the mother to censor explicit material like gore and pornography before her very eyes.

As with Men Against Fire, neural implants simply haven’t reached this degree of sophistication, and there’s no reason to believe they will in the foreseeable future. That said, several comparable child surveillance devices and software exist. Amongst the most intrusive is mSPY, a tracking software which can not only be installed remotely but enables access to the target user’s social media profiles, private messages (both SMS and over Messenger/WhatsApp), browser history (including incognito searches), and Tinder usage. It doesn’t stop there; it comes with keylogging software ÔÇô which feeds through exactly what the target types on their keyboard ÔÇô in addition to GPS tracking and geofencing, which alerts the remote user when the target leaves a designated perimeter. The worst part is that it operates silently in the background, meaning the target user has no way of knowing this software is even monitoring them (save for the minority of particularly tech-savvy kids).

Most concerningly, mSPY has won multiple awards in the USA, despite the fact that 85% of domestic violence shelters claim to house victims tracked by equivalent software. Oh, and its security is borderline non-existent as well, meaning you compromise your child’s online security and privacy even more than the app already does for you. It truly is nectar for delusional helicopter parents.

Though Arkangel makes an astute commentary on invasive parenting, mSPY and its contemporaries have been around since the mid-2010s, meaning the episode wins no points for prophecy.

Crocodile (2017) ÔÇô 3/10

In Crocodile, accessory to murder Mia Nolan kills a series of innocents to cover her tracks. The tech in play here is the ÔÇÿrecaller’, a device capable of extracting and playing back memories, which Mia uses to verify witnesses before murdering them. Given its focus on memory playback, it’s conceptually similar to The Entire History of You, but Crocodile goes a step further by explaining how the technology actually functions, giving us more to work with.

According to the episode, the recaller accesses engrams in the mind which, whilst not entirely accurate, help ÔÇÿbuild a corroborative picture’. Engrams are real, but they’re not as simple as a video file that can be played with the right device. Instead, engrams are the changes our brain undergoes when it experiences something. Whenever we encounter something memorable, some of our neurons fire up in reaction. Take the example of meeting someone new. At the time, a combination of neurons in your brain would have activated, and this same combination of neurons would activate if you saw them again. An engram, then, is simply the combination of neurons our brain stimulates to remind us what we’re looking at.

But can engrams be ÔÇÿread into’ with a device? The answer is a resounding ÔÇÿsort of’. Miniscopes can examine engrams directly and have been used to accurately ÔÇÿread the mind’ of a rat, but not in the way you might think. Scientists monitor which of the rat’s neurons light up in response to stimuli, and based on that data, they can accurately understand what the rat was doing ÔÇô even down to which routes it took when travelling ÔÇô just by looking at the combination of engaged neurons.

If a real life recaller were to exist, it wouldn’t provide a visual memory, or the telepathic extraction of knowledge traditionally associated with mind readers in science fiction. Amongst the biggest obstacles, Dr Blake Porter of the University of Otago argues, is device memory. ÔÇÿThe biggest issue [is] somehow getting enough neural data [to decode an entire memory] from such a small device’. Physics is against us as well; neural signals decay rapidly as they traverse the brain, which at this point has no solution.

Regardless, the notions that this technology would ever be as precise as Crocodile’s recaller, pick up on Mia’s irrelevant murder, or be used in the justice system, or draw compelling evidence of a murder from a gerbil, are utter fiction.

Hang the DJ (2017) ÔÇô 3/10

In Hang the DJ, Frank and Amy match on a dating app with a compatibility score of 99.8%. This score is generated by placing their digital clones in a sophisticated simulation of a gated community wherein an AI constantly matches them with dates, one of which will be each other. The simulation is run a thousand times, and the percentage of simulations which result in the clones rejecting the system and running away together is used as a compatibility score for the real-life app.

Whilst such an elaborate simulation could not exist for similar reasons to White Christmas’ cookie technology, attempts to algorithmically calculate compatibility exist. Whilst Tinder has undergone a litany of algorithmic changes over the years, it now opts for the rudimentary system of flooding the queue with the most ÔÇÿattractive’ users in your immediate vicinity, based on how everyone around you is swiping. Whilst Bumble allows you to filter out other users by height, political leaning, substance use, and other characteristics, the matching algorithm works mostly the same way as Tinder’s.

The only significant dating app whose algorithm attempts to determine compatibility is Hinge. Hinge asks users to answer three miscellaneous questions (for instance, ÔÇÿwhat’s your ideal night in?’), and tries to match users based on the compatibility of both their responses to these questions and other basic filters akin to Bumble. The algorithm Hinge uses to determine compatibility is based on the Gale-Shapley algorithm, which, to simplify beyond justice, tries to create the most ÔÇÿstable’ match between various parties with differing levels of preference towards one another. The algorithm basically tries to achieve ÔÇÿstable’ matches for as many users as possible by matching them with users who are likely to express a mutual degree of preference towards one another that is greater than their preference for a significant number of other users.

Hinge originally came out in 2012, but it didn’t enter the public consciousness until 2018, when Match Group ÔÇô the owners of Tinder, OKCupid, and others ÔÇô became majority shareholders in the company. So, points to Hang the DJ for guessing that algorithm-based compatibility in dating would become more important, but the simulation stuff has no basis in reality.

Metalhead (2017) ÔÇô 8/10

In Metalhead, a woman runs away from a dog-like robot in a post-apocalyptic world ravaged by killing machines. That’s, uh, about it.

Do killer robots exist? Yes ÔÇô but very few, if any of them, have the autonomy of Metalhead’s dog robot. Most of them are controlled remotely by operators, such as UCAV drones which perform reconnaissance and launch air strikes. Genuinely autonomous lethal weapons are usually defence systems programmed to intercept projectiles and enemy aircraft, like the Goalkeeper CIWS; these have existed since the 1970s.

Autonomous offensive weapons do exist, but this is different to a truly autonomous military robot. Rather, autonomous weapons in their current state can perform various combat functions without human input, but they don’t engage targets without supervision. In short, killer robots capable of independently acquiring and attacking targets exist, but their deployment remains a matter of contentious debate. The Future of Life Institute has condemned lethal autonomous weapons (LAWs), and Tesla CEO Elon Musk was among 116 experts to call for an outright ban on LAWs, both stating that technology cannot be trusted with the morbid decision of adequately distinguishing targets from civilians. Other concerns include the misappropriation of LAWs by terrorists and the global acceleration of warfare that such technologies would provide.

In response, major military superpowers across the world, such as the USA, UK, Russia, and China, in addition to smaller militaristic nations like Israel, have all accelerated development on LAWs because humanity is dreadful.

The robot dog from Metalhead specifically is based on BigDog, a real robot dog developed in the USA, but DARPA stopped funding it when they realised it was too loud and too clumsy for combat. I’d argue he still deserves to be rubbed and told he’s a good boy.

Black Museum ÔÇô 2/10

Black Museum mostly consists of the same kind of consciousness transfer technologies we discussed earlier, but there is one piece of kit worth touching on. One of Black Museum’s narratives focuses on a doctor who uses an implant to feel the pain of his patients, allowing him to diagnose with greater accuracy. He then discovers that he’s a major masochist because the thrill of experiencing death and pain vicariously turns out to be a huge turn-on.

Whilst the 1:1 transmission of pain from one person to another is a long way off, sensory simulation is a real thing that’s gained traction in recent years. In Eastern China, some hospitals offer fathers the opportunity to use voluntary electrode torture to simulate the pain of childbirth. In what is surely a shocking twist, they didn’t like it very much.

Bandersnatch – 11/10

In Bandersnatch, Black Mirror‘s interactive episode, a young game developer (Stefan) adapts a multiple-choice adventure book into a text adventure game. He ends up embroiled on a wild ride that takes him through multiverse theory and alternate timelines. At one point in the episode, Colin, a mysterious games industry legend, introduces Stefan to the concept of each action creating multiple timelines by jumping off his highrise balcony, becoming pavement pasta in the process. To verify this theory, I had one of Quench’s most dedicated journalists leap from our office, and since I haven’t heard from them in a while, I can only assume they found themselves in another timeline, convincingly verifying the episode’s theoretical standpoint.

Striking Vipers ÔÇô 8/10

In Striking Vipers, two friends reconnect over their old love for fighting games by buying Striking Vipers, a fancy new VR knock-off of Tekken. But there’s a twist ÔÇô this one allows you to do anything you like in that space, not just the character’s special moves. You also experience the physical sensations of your character. If you haven’t cottoned onto Charlie Brooker’s randy mind yet, I’ll do the maths for you: they become smash bros.

Since we’ve already established that the neural implant technology that facilitates a game of Striking Vipers is out of reach, one question remains: can you bone in VR? Not yet ÔÇô but it could definitely get there. There are haptic bodysuits which simulate the sensation of touch through electrical stimulation, and it’s not hard to imagine a future where this technology finds a niche in sexual multiplayer. It could even be a powerful tool to achieve sexual interaction in long-distance relationships. Apps to remotely control sex toys exist for that exact purpose, so the market is there.

The issue is that this sort of thing would never worm its way into a fighting game with public matchmaking. Imagine the legal and ethical quagmire of getting into a game of Street Fighter and knowing that at any moment, your opponent could either hadouken or do Ken. The risk of sexual impropriety would be astronomical.

Smithereens ÔÇô 0/10

In Smithereens, a man loses his fianc├®e to a phone-related car accident and joins the boomer crusade of ÔÇÿphones bad’. Like Shut Up and Dance, it’s set in the present day, so it doesn’t offer a glimpse of the future at all.

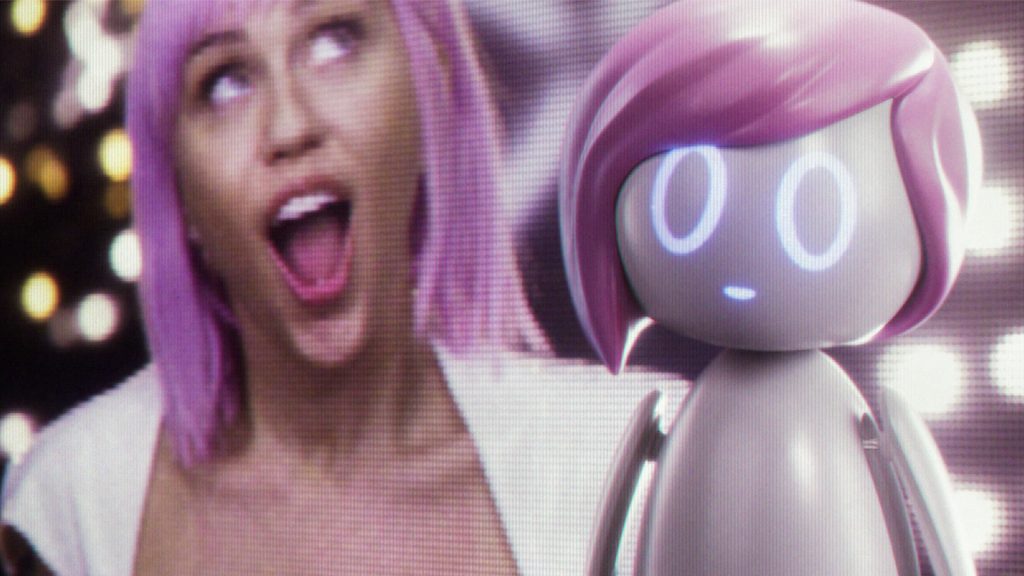

Rachel, Jack, and Ashley Too ÔÇô 3/10

In Rachel, Jack, and Ashley Too, pop superstar Ashley O is exploited so hard by corporate greed that they:

- Release a robot companion device with her consciousness inside

- Use that consciousness to host performances of her hologram

- Use her comatose mind to produce new music

From White Christmas, we can write off the possibility of a cloned conscious robot companion straight away. As for the coma stuff, there’s nowhere near enough brain activity in comatose patients for Ashley’s corporate overlords to extract songs from her. The hologram is a real thing though; in fact, Amy Winehouse, who died in 2011, almost went on tour in 2019 before a series of controversies and technical issues has left the project in limbo. Whilst the Winehouse hologram is approaching commercial use, the technology is nowhere near as sophisticated as the glimpse we see in Black Mirror. Much of its behaviours aren’t simulated from Winehouse herself, but instead draws from footage of an actress hired to replicate Winehouse’s performances as precisely as possible.

The ethics of posthumous hologram tours remain hotly contested. Whilst they may be considered distasteful by many, the legality of the issue is that the owner of the subject’s likeness merely needs to consent, so hologram tours may not be too far off after all.

The Verdict

We’ve come a long way, you and I. Together, we learned about transposing the human consciousness, social credit systems in authoritarian nations, quantifying romantic compatibility, shapeshifting robot sex, implants and engrams, the contextual importance of knowing the difference between ÔÇÿshoryuken’ and ÔÇÿsure you can’, and so much more.

What can we take away from all this? Excluding Bandersnatch, Black Mirror‘s overall prophecy score (based on the average of each episode’s rating) was 3.3/10. But, to be a bit fairer, if we exclude all the episodes that clearly aren’t based in the future ÔÇô The National Anthem, White Bear, Shut Up and Dance, and Smithereens ÔÇô Black Mirror earns a much more impressive 4/10.

So, just how prophetic is Black Mirror? After all that, the answer, my friends, is: somewhat, occasionally. Was Black Mirror even trying to be prophetic in the first place? No, says Charlie Brooker, ÔÇÿthey’re not societal warnings’. Was this whole endeavour, then, a disingenuous assessment of an artist’s success in achieving a goal he never pursued in the first place? Perhaps. Did you just waste your life reading half a dissertation of trivia that’s not even workplace-appropriate enough to make you seem knowledgeable without coming off as a bit of a weirdo? Probably. Has researching this article involved multiple Google searches that will get me in big trouble with GCHQ? Absolutely. But what matters is that you can walk away from this knowing that no matter what, your great great grandchildren will have full-body sex with their dead android exes in Tekken whilst their mum watches the whole thing on her iPad.