By Phoebe Bowers

Categorised often to be corny, clich├®d or formulaic, the horror genre has been overlooked in terms of its sustainability and versatility. Horror over the years has spawned itself into several sub-genres from gothic, to silent, to slasher, to supernatural, to ÔÇÿfound-footage.’ It has birthed some of the most iconic film scenes to-date. We┬á don’t even need to name the film where the image of a flung shower-curtain and blood running down a plug-hole comes from; one automatically knows where this scene is from even if they have never watched Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). Moreover not only scenes from the horror genre, but scores from the genre are so recognisable, one does not even need to have seen the movie Jaws (1975), but is able to match the film to┬áits famous two-note motif instantaneously. It is apparent that the genre does not really appear to have a ÔÇÿshelf-life’, and has the ability to relentlessly ingrain itself in our minds. This vast genre is continuously producing more and more scare tactics through camera movement, lighting, storyline or setting. Horror’s ability to continuously evolve stylistically appears to be the root of its timelessness and popularity.

Looking back from the ÔÇÿLiterary Years’ of horror film (roughly 1900-1920s) up until the present,┬á despite the ever-changing eras and sub-genres horror itself galvinises and generates, the plot of horror appears to have come full circle.

This is in regard to the horrific content being a direct reflection or parallel of the uncertain political landscapes that surround us in reality.

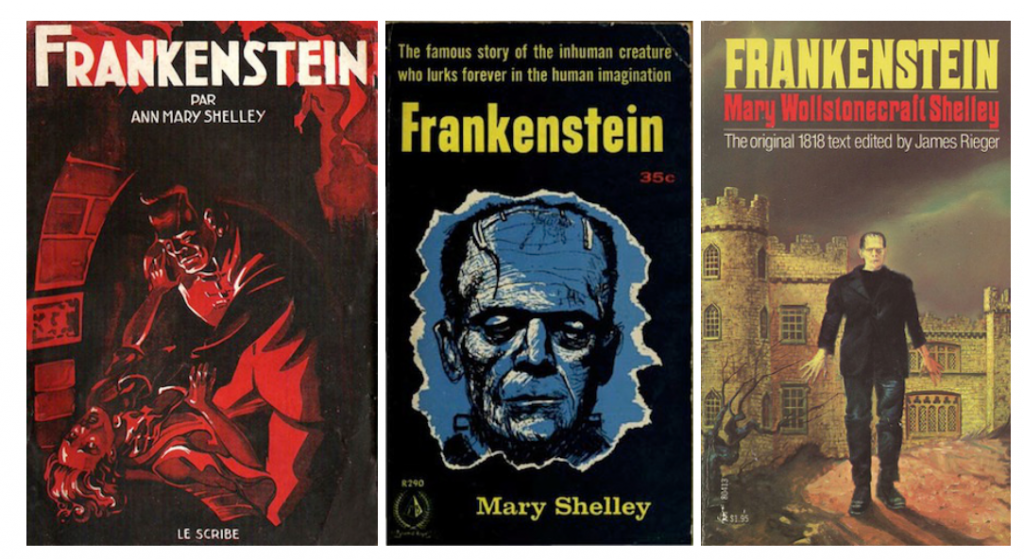

The ÔÇÿLiterary Years’ of horror included the likes of various literary-film adaptations of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Bram Stoker’s Dracula, or Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. These literary texts were all about conservative fears over revolution and reformation in the light of Scientific Enlightenment or Industrial Revolution in the case of Frankenstein and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Frankenstein’s monster and Mr Hyde are the monstrous personifications of fears of scientific and technological pursuits of the future. These monsters perpetuate metaphorical anxieties into scary physical bodily entities. Dracula represents fears of globalisation, the sub-human creature being this xenophobic physical manifestation – a horrific murderous representation of the ÔÇÿother.’ This archetype of the horror genre reflecting temporal societal anxieties has bled through the ages.

It has been overseen in the ÔÇÿAtomic Years’ of the 1940s-1950s whereby films such as Godzilla (1954) and The War of the Worlds (1953) paralleled real-life fears of Atomic warfare. With the threat of the Cold War looming in the background of mundane life, radio-active mutations such as Godzilla or expansionist opposing ÔÇÿalien’ societies – although outlandish – had very real anxieties behind these kooky manifestations. Another instance is ÔÇÿSlasher’ horror being popularised due to the exponential popularity of True Crime. Figures like Bundy or Manson inspired the horrific content of these movies to be serial killers, as it was no longer a scientific experiment gone wrong or Communist invasion audiences were afraid of – but real people simply living amongst them.

Today real life legitimate societal fears are still being manifested or metaphorically represented in horror, but with a refreshing twist. A stark example of this being utilised is by director and writer Jordan Peele in his films Get Out  (2017) and Us (2019).

‘The horror in these movies┬áis systemic racism in our culture and our inherent fear of the ÔÇÿother’ in a new form: fears of migration, fears of the ÔÇÿother’ becoming ÔÇÿus’ if you will.’

Peele’s use of ÔÇÿpoint of view’ camera angles and shots creates a rather personal viewership, which in turn creates an eerie distancing between us and the ÔÇÿother.’ The purpose and impact of this being that these insidious prejudices in the world are taught and inherent and unconscious within ourselves; and although we may not believe to withhold any sinister views about other people, we do actually demonstrate them.┬á

Since horror film’s immemorial, lighting has had a significant influence on what makes horror films ÔÇÿscary.’ The birth of horror of course originating from Gothic source material, it is often the use of purposefully very dark lighting that is made to scare us. The dark that obstructs our senses and┬á limits us is home to the unknown. However the ÔÇÿmodern’ horror film has shown to deviate from this convention.

Ari Aster’s Midsommar (2019) was┬áa horror set in broad daylight. There is no darkness to obstruct from the brutal violence or gore on the screen. All of it is on show. The constant vibrancy of the light instead causes this sense of delirium as time seems to be┬ástill. Day and night blur into one. Aster then instead relies heavily into creating a sense of dread and anticipation to evoke fear. It is the fear of what the plot is moving towards, the film’s final denouement then proving to be greatly disturbing. Aster moreover seems to deviate from the orthodox not just with lighting, but with his camera shots. He frequently utilises close-up shots in his works. What we then witness are these raw, drawn-out, excruciating terrified reactions of his actors instead of the predictable ÔÇÿjump-scares’ used in supernatural horror. In Midsommar there is a stand-out scene, where the camera is unmoving from Florence Pugh’s face as she lets out this rather guttural uncontrollable sob as the women around her scream. This is something Aster also included in his debut major film-feature Hereditary (2018) where Toni Colette’s screaming face has become a cultish sort of icon for the film. These close-up shots seem to merge the likes of a Hitchcockian ÔÇÿscream queen’ with a Kubrick stare, similar to Jack Nicholson’s unnerving prolonged stare at the camera in The Shining (1980).┬á

On the whole, it seems to be that horror has overseen a lot of change and continuity in regards to how it chooses to scare its audiences. Although the genre does include a lot of re-hashed tropes, the genre seems to be ever-experimental and ever-changing. Who knows how it will change next stylistically? If, as usual, it will project our temporal fears in this uncertain and unprecedented time, I predict perhaps a re-emergence of cabin fever horror inspired by lockdown.