By Mike O’Brien

Warning: This article contains major spoilers for Red Dead Redemption 2 and Spec Ops: The Line, and minor spoilers for Grand Theft Auto IV.

In 1969, Mario Puzo wrote a novel called The Godfather. Despite his working-class heritage in Hell’s Kitchen, Puzo’s hobbies included lavish six-course meals and ignoring the bill. Fortunately, he was a magazine staffer at a mythical time in the distant past when writers earned a disposable income. Eventually, Puzo’s avarice grew so reckless that his cheques bounced on a platinum trampoline. A novice to long-form fiction, Puzo’s The Godfather was a shamelessly expedient cash-grab, and he cared far less for the novel than he did for his $5k advance. The Godfather would go on to make a little more than that. Waxing pensively on a diamond bidet, Puzo eventually developed an interest in learning how to be a ÔÇÿreal author’, so he picked up a book on storytelling. The first line of advice was: ÔÇÿread The Godfather‘.

History venerates the inaugural triumphs of Mario Puzo and Mary Shelley because there’s a romantic allure to stories leaping seamlessly from thoughts to ink. But for every Harper Lee, there’s a hundred thousand tortured authors bemoaning that their passion lacks the same transmutable fluidity. Eventually they face the music: it’s a myth. The Godfather was a full-time, three-year slog to write off a bad debt. Storytelling is a learned discipline, a science, a process with laws and rules, even if it draws from the soul. The sovereignty of the author is absolute. They have divine authority over the thoughts and actions of everyone in their universe, and the perspective through which it is experienced. Even with this power, producing a linear story that enriches, ensnares, and sparks ideological conflict is an industrial effort. How on earth, then, do writers approach the narrative of a video game, where the player hijacks control of the main character?

1899. The American frontier’s harshest tundra bellows with the bite of a glacial tempest. Trudging forth is a candlelit caravan of misfits and outlaws dimming under snowfall. Mothers cradle their sons from the cold, convoyed through the blizzard by stoic gunslingers on lookout for the law. They march behind Dutch Van der Linde, their eccentric and intellectual surrogate father, whose fanciful promise of a Caribbean arcadia is the only hope for this flock of strays and bastards. As stomachs turn and the night unfurls, the group’s grief-stricken silence is eroded by frightened murmurs about the girl Dutch killed at Blackwater Bank.

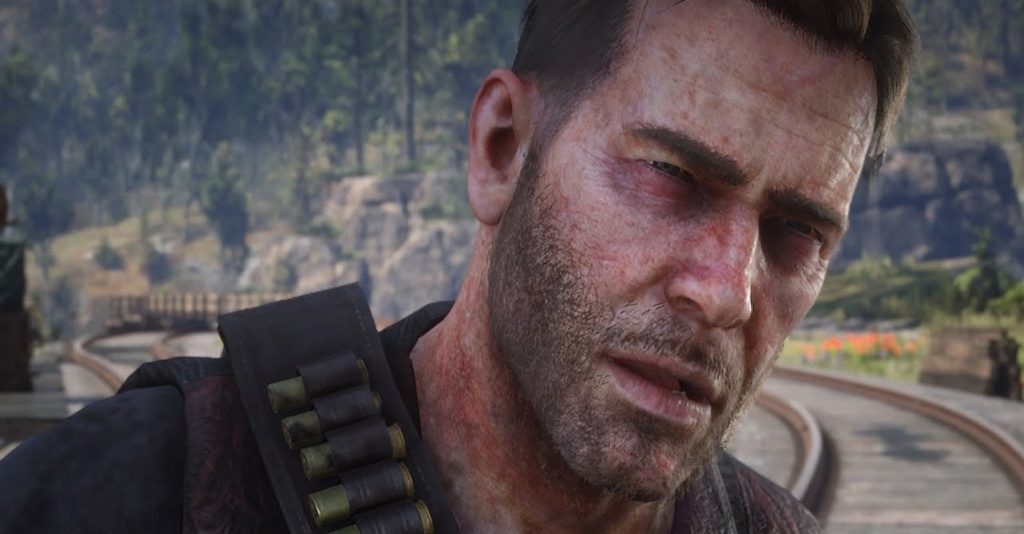

This is Rockstar Games’ Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018), a tale of the dying wild west’s last outlaws whose annihilation at the hands of federalism is imminent. There are two parts to this game; the linear narrative, which is a series of ÔÇÿmissions’ that lead the player through scripted sequences (like episodes of a TV show), and the open world, which players can explore and interact with at their leisure. The central theme is anarchy versus civilization, embodied by the decaying relationship between the player character, loyal outlaw Arthur Morgan, and Dutch Van der Linde, the noble savage who raised him. The conflict is primarily escalated by key events in the game’s linear story, where, as Dutch’s increasingly catastrophic and ideological schemes endanger the gang, his communal vision of growing mangoes in Tahiti subsides into myth. When the gang runs out of places to hide, paranoia corrupts Dutch into a man Arthur no longer believes in, a tyrannical patriarch and a failed ideologue whose raison d’├¬tre disintegrates to ash.

Amongst Red Dead’s grandest achievements is the way it uses gameplay and dynamic space as narrative devices, something only the interactivity of a video game can offer. Arthur’s doubt in Dutch is not only developed by the linear story, but informed by the player’s self-determined journey through the open world. In the first act, the Van der Linde gang are cosy vagrants. They set up camp atop a quaint hill surrounded by gorgeous plains, teeming with small prey and luscious flora. When the player diverges from the camp and charts their own course, approaching, say, the gorgeous vista of a distant snowy mountain, they learn through the experience of play that nature beyond civilization’s grasp is not all that it seems. The player’s hand is eternally holster-bound. They never know whether the horseback silhouette hurtling towards them will tip their hat in passing or murder them for sport. Wolves leap from the snow, alligators lurch in the water, even the elements are hostile to life and demand adaptation. The one exception is the town of Saint Denis, an industrial district sprawling with smog, soot, and the law. It’s miserable, ugly, unromantic, and worst of all according to Dutch, ‘civilized‘. But funnily enough, it’s the only sanctuary the player can find. When the player returns to camp to resume the linear story, and Arthur’s squint narrows at Dutch’s proselytizing glibness on the tranquility of nature versus the sins of civilization, his cynicism is organically reinforced by the player’s self-led journey.

Player agency, in this respect, can give credence to a story. In most cases, however, the writer’s vision and the player’s freedom are wildly irreconcilable. Arthur’s doubt in Dutch plateaus when he needlessly strangles a woman to death whom they’d struck a deal with. Hereafter, Arthur charges Dutch with murder. Of all the key story beats, it is the final impetus behind the death of Arthur’s loyalty. The issue is that this conflict is endangered by the absolute freedom players have over Arthur’s behaviour in the open world. At any point, the player can have Arthur ride into town, hogtie a suffragette, and dump her helplessly on a train track before reducing her to viscera. Players can even have Arthur wisecrack contextually as the train approaches. This single act eclipses any of Dutch’s transgressions by a landslide, and it completely invalidates the narrative’s central conflict. If Red Dead Redemption 2 were a film, and at some point, Arthur threw a civilian into his own campfire for amusement, only to then chastise Dutch for mindless murder in the next scene, critics would rightfully tear it asunder. Yet, Red Dead Redemption 2 ranks amongst the highest-rated games of all time on aggregator sites, and its critics, including myself, couldn’t shut up about its fantastic narrative.

This disconnect between the events of the linear story and the player’s freedom to act is called ludonarrative dissonance. For many gamers, it’s no issue; they’re happy to compartmentalize these two parts of the game as divorced entities with no consequential relationship. Others accept ludonarrative dissonance as an unavoidable caveat of games with plenty of player freedom. Neither of these perspectives are healthy for the games industry. Ludonarrative dissonance is not an intrinsic limitation of the medium, it is the failure of writers to coalesce the gameplay and the story into one vision. Until gamers and critics recognise this, the industry will continue to settle for lower standards of writing. If you believe video games deserve the same artistic recognition as its contemporaries, then you must agree that they face the same standard of criticism.

Frustratingly, the apparatus required to rectify Red Dead Redemption 2‘s ludonarrative dissonance is already in the game ÔÇô it’s just painfully underutilised. The game has an ÔÇÿhonour’ rating that alters based on how the player behaves in the open world. Give an injured stranger a ride back to town, gain honour. Lobotomize them with a sawed-off, lose honour. Your honour alters some of Arthur’s dialogue in the linear story, but these changes only soothe his cadence; the differences are nominal with no bearing on the plot. Red Dead Redemption 2 could have fixed its entire ludonarrative dissonance issue with just one exchange. The game is full of horse-riding sequences which the writers use to dump expositional dialogue. In one of these, include a conversation between Arthur and another sceptical gang member whereby he concedes that, even though he is a recklessly brutal man, Arthur admires Dutch for his moral integrity, that Dutch is the man Arthur failed to be. By making this exchange exclusive to dishonourable players, it not only legitimizes the honour system with meaningful consequences, it contextualises everything the player can do of their own volition. As the game is, players who act dishonourably in the open world must conjure justifications out of thin air. This is a failure to weave action into character, not a limitation of the video game medium.

Red Dead’s dissonance is baffling given that Grand Theft Auto IV is a masterclass on synergizing player agency and narrative ÔÇô a game Rockstar released ten years earlier. Hailing from a franchise infamous among Republican puritans for its prostitutes, car chases, and wanton massacres, Grand Theft Auto IV is in fact a scathing, mature, and eloquent indictment of the American dream. It’s no less a game than it is an interactive time capsule of a bygone decade; wandering its bleak imagining of post-recession New York already feels like ambling in ancient history. The player character is Niko Bellic, an illegal Serbian immigrant lured to New York by promising letters of wealth and luxury from his cousin Roman. When Roman arrives at the docks in a filthy cab reeking of liquor, Niko discovers the ÔÇÿmansion’ is a roach-infested apartment in Hove Beach, a Slavic ghetto, where Roman’s gambling addiction has invoked the wrath of Vlad, a vicious Russian loan shark. To pay off Roman’s ÔÇÿdebt’, Niko runs criminal errands for Vlad until he discovers that he’s been sleeping with Roman’s girlfriend.

Grand Theft Auto IV is seldom mentioned in today’s critical discourse, but ÔÇÿUncle Vlad’ is amongst the most well-written missions in video game history. In a rush of indomitable anger, Niko, deaf to a desperate Roman pleading for calm, murders Vlad in cold blood. Niko’s demeanour thereafter is jarringly apathetic; whilst dragging the body, he even mocks the weight of Vlad’s corpse. Roman, in contrast, is frantic with fear, petrified of mafia retribution, and horrified by his cousin’s indifference to death. Niko soberly reveals that he was a child soldier in the Bosnian War, and that the real reason he’s come to America is to pursue a former squad member who led him to an ambush for cash. A bemused Roman damns Niko, claiming that his obsession with correcting the past has left him desensitized to the lives he ruins along the way.

ÔÇÿUncle Vlad’ alone conquers ludonarrative dissonance. Niko is Thanatos, an agent of death, a man enslaved by trauma with no regard for his own life. Psychosis and post-traumatic stress disorder flood his will like viscous tar oozing in the canals of his mind. Should the player abruptly swerve into oncoming traffic or pave the streets with pedestrian blood, these extreme behaviours make twisted sense. Niko’s dissociative tendencies and mental illness render him an unreliable psychotic narrator, which weaves the game mechanic of respawning after death into the narrative. When the player ÔÇÿdies’ in a police shootout in the open world, only to emerge thereafter from the nearest hospital, who’s to say the carnage even occurred outside the delusions of a psychotic episode? The icing on the cake is that despite all this, Niko remains the most sympathetic and memorable character Rockstar has ever written. He is self-aware, vulnerable, unpretentious, and indentured to protecting the few who show him love. He is anathema to the American dream, a cynic with a tragic vendetta against the corrosive influence of money. That Grand Theft Auto IV achieves all of this without compromising its trademark sinful sandbox is a testament to the power of thoughtful writing.

Great writers can circumvent ludonarrative dissonance at every corner. But for exceptional writers, ludonarrative dissonance isn’t a problem: it’s a weapon. The early 2010s were overwhelmingly saturated with monochromatic military shooter games. Electronic Arts was pushing Battlefield and Medal of Honor, Activision was pushing Call of Duty, THQ was pushing HomefrontÔǪ it was an unavoidable and, worse yet, unimaginative, pandemic. To their credit, many of these games were well designed and mechanically robust, just horribly written. Their narratives revolve around Osama Benito Mikhail Mohammed Baghdadi Jong-Un, a terrifying super-Muslim commie dictator hellbent on world domination, and the only solution is for the brave US military to invade whatever orientalist fever dream of a third world country he comes from. When Yager Development released Spec Ops: The Line (2012), its promotional material suggested it would be yet another pointless US military romp. This time, cataclysmic sandstorms have totalled Dubai, and a rogue US infantry battalion, the Damned 33rd, has declared martial law over the city and its survivors. You play as generic white soldier man Cole Walker and his two best military buds Adams and Lugo, a spec-ops trio sent to exact Uncle Sam’s justice and save Dubai.

For a few hours, the game is a painfully average third-person shooter ride, a flaccid rollercoaster of hell-yeahs and high-fives as you mow down hordes of pesky Dubaians and 33rd soldiers. Eventually, the player encounters a base with far too many enemies to take on at once, so Walker and the boys decide to bust out the drone for the obligatory ÔÇÿvehicle mission’ clich├®, raining white phosphorous and one-liners on the 33rd. Wading through the aftermath, Walker and his comrades advance on the camp to find a surviving soldier, his face unrecognisably charred, uttering a single word: ÔÇÿwhy?’. Walker turns to find a mother shielding her child’s eyes, flesh blistered and scorched, their corpses immortalised in cinders. The trio realise they’ve deployed chemical weapons on a refugee camp, murdering 47 civilians. Adams and Lugo descend into panic and guilt ÔÇô but Walker pushes on, blaming the 33rd in denial and vowing to take them down.

Walker is a psychopath with a hero complex, and to continue the game, the player must occasionally choose between committing one war crime or another. Regardless, Walker denies accountability, and the game berates you for your actions. Past a certain point, the game’s loading screens, which usually offer tips on how to play the game, instead read: ÔÇÿThe United States Army does not condone the killing of unarmed combatants. But this isn’t real, so why should you care?’. Spec Ops: The Line left a sour aftertaste in the mouths of defensive gamers. It’s unfair that players face umbrage for Walker’s actions when all the available choices produce identically horrific effects. What’s more, for a game that scolds the player for mass murder, the gameplay loop consists of nothing else. Just like Call of Duty, the appeal of Spec Ops: The Line’s gameplay is the gratification of virtual killing. On the face of it, this is unfairly punitive ludonarrative dissonance; how can the player be held accountable for any of this? Well, Spec Ops: The Line argues, the player had another choice all along: to stop playing.

Yager Development knew what kind of person their action-packed, hyper-masculine trailers were attracting: people who wanted a mindless patriotic ÔÇÿhooah!’ through the sand. It blames you for indulging in myopic celebrations of imperialism that dismiss the human cost and moral complexities of warfare. In the same way the player actively enables Walker’s atrocities to keep playing their video game, we, too, are desensitized to the war crimes of our militaries. Indeed, our passivity as comfortably numb and distant consumers enables men like Walker to scorch the earth. “The truth is,”, the game’s antagonist tells Walker, “you are here because you wanted to feel like something you’re not: A hero.” At the end of the game, Walker, who by now barely resembles a human being, gazes over the Dubai he ruined, and the game asks: ÔÇÿdo you feel like a hero yet?’

Grand Theft Auto IV and Spec Ops: The Line are just two of many case studies which prove that storytelling and player agency . Many qualities separate a good video game from a great one, but the most crucial is how well it answers this question: did this need to be a video game to achieve its goals? Spec Ops: The Line couldn’t have been anything else. Its meta-narrative on choice and compliance is entirely dependent on the interactivity of video games, and as such, it fully maximises the unique strengths of the medium. It is profoundly sad, then, that for all the games industry’s artistic progress, many mainstream critics fail to acknowledge ludonarrative dissonance in their reviews. Writers aiming to deliver an impactful linear narrative should be pressured to align the freedoms of the player with the themes of their character, lest the game becomes a fractured vision. It is the responsibility of critics to encourage these standards, and anyone who truly cares for the growth of art must surely agree.