Words by Lewis Empson, Marcus Yeatman-Crouch, Ona Ojo and Alex Payne

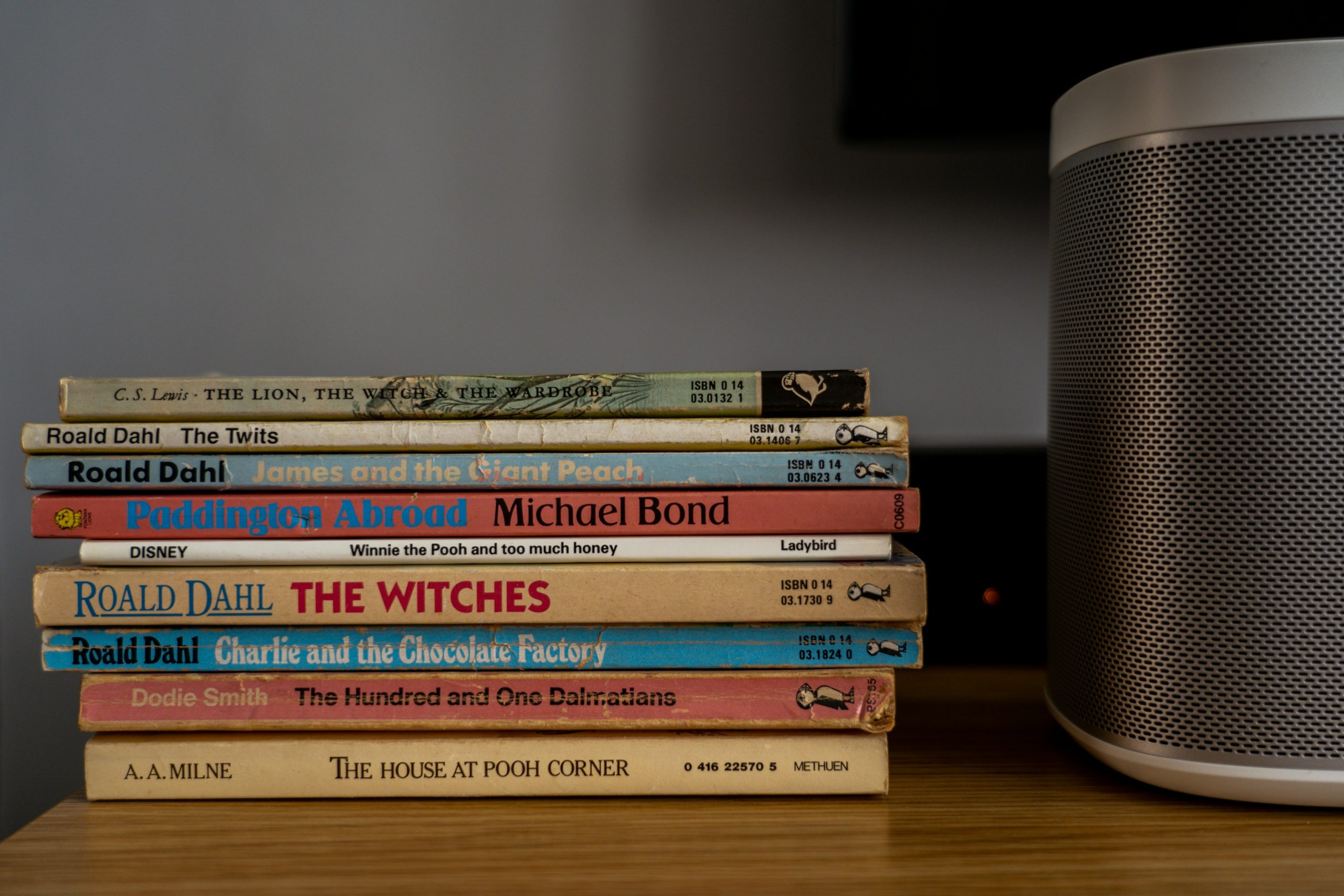

Cover image by Gio Bartlett via Unsplash

A while back we discussed how the video gaming industry is undergoing a major transformation in how gamers own the games that they play. As the cartridge became the disk, the disk is quickly being forgone in favour of digital game marketplaces and streaming services – as evidenced by the Xbox Series S and PS5 All-Digital Edition. Thanks to undeniably fantastic digital alternatives to owning physical copies such as Xbox Game Pass and (to a lesser extent) PS Now, the entire landscape is changing; as of April 20th 2021, Xbox Game Pass has over 23 million subscribers.

Now this physical to digital shift may be a phenomenon that we’ve already explored in the gaming sector, however, it has been long evolving in various other media formats with digital/streaming services dominating the world of music, film, television and books for many years now. Spotify playlists have assumed the role once occupied by records, mixtapes and compilation CDs, Netflix and Disney+ are the go-to spots for film night thanks to unending options that DVD collections just can’t compete with, and Amazon’s Kindle platform is the biggest bookstore in the world from which you can read on any device you choose.

Choice and convenience are the two biggest strengths of streaming services in the digital age, with users being able to access practically any book, show or song whenever and wherever they want, often with a monthly subscription price that may be more attainable than splashing out £10 for a single DVD when a whole month of Netflix is the same price. Consumer choice is at the forefront as content is being constantly added to these platforms and are ready to be accessed whenever without the need to even leave the house.

But we’re also here to talk about the ownership of the media that we love: these streaming services may be a platform to watch, read and listen – but what happens when these platforms go down? Or what if your favourite movie or song is removed? This is why physical ownership of our favourite media is so important to many; tangible copies can never be removed from a platform, hard drive or server. Physical media can be shared, borrowed and sold in ways that digital media cannot, which benefits those who rely on more affordable options to access media as well as those who want to sell their copies to enjoy new media. And what about independent music and book shops? Their very existence depends on physical releases and to many these are the heart and soul of their communities.

So it’s important for consumers and industries to keep physical media alive, even if digital ownership and subscription services are the “future”, there are unique aspects that pertain to the relationship between physical media, consumers and the industry that ties these together. Here we have some perspectives from our Quench comrades as to how digital and physical ownership relates to their section and industry:

Marcus Yeatman-Crouch – (on behalf of) Film and Television:

“You’d be hard pressed to find an industry more changed by the move to digital media and subscriptions than film. It has to be said, it’s a lot easier to just pay ÔÇÿx’ amount a month and have access to hundreds of films and TV shows than popping down to your local rental shop and taking out a few DVDs you have to return in a couple of weeks. Rental shops are now a bit of a novelty, while their successors have shot right up in the list of almost essentials when sourcing entertainment. It’s likely that you and your family or friends have amassed a bit of a collection of subscriptions, what with Netflix, Disney+, Amazon Prime and others providing exclusives and classics you can go back to whenever you want.

Subscription streaming is certainly the future, and the pandemic has only cemented that view given the inability to go to the cinema or get physical copies of films. Many blockbusters have resorted to a streaming debut, the biggest probably being Zack Snyder’s Justice League cut, which at 4 hours would be a bit of a stretch to fit into a normal cinema experience. The same goes for Raya and the Last Dragon on Disney+ and Wonder Woman 1984, both well received movies that had to forego the traditional cinematic release. That’s not to say film buffs are happy with the transition. Martin Scorsese notably critiqued streaming for devaluing movies, but we’re sure there are plenty who would prefer the event of seeing a movie at the cinema over everything being released on streaming. That’s why hybrid releases are now being embraced, with future movies such as Marvel’s Black Widow getting both cinematic and streaming releases on the same day.

The transition to digital isn’t exactly killing movies or TV – really it’s still thriving, and there’s more opportunity for low budget content to make it onto the same page as the biggest Hollywood movies when they’re not relying on cinema sales. The pandemic has thrown the future of the cinema into doubt a little, but we think there’s enough appreciators out there that streaming will never truly take over that classic experience.”

Ona Ojo – Literature:

“The use of e-books has grown exponentially over the last decade, sparked by the launch of the Kindle in 2007 and the iPad in 2010. Digital forms of literature are a positive stride for many reasons: ease, accessibility, and affordability (minus that initial investment if you choose an e-reader). Many e-books take advantage of digital tools like animation or audio to make their content more interactive.

They also increase visibility for self-published authors, often a more diverse group than those in traditional publishing. But to me, and many other book-lovers, there is an everlasting appeal to physical books. I read tons of e-books every year, and yet when I finish something I’ve really enjoyed, a potential favourite, my first instinct is to add it to my collection. For me, part of the reading experience is owning – or at least borrowing – that physical work. And despite the series of lockdowns last year, print book sales in the UK grew an estimated 5.2% from 2019, bringing in almost ┬ú1.8 billion. Many people, myself included, bought more physical books in 2020 than in any year before. With school, work, and even social interactions moving primarily online, print books were an escape from screen fatigue.

Digital media has transformed literature – authors can reach a larger audience, books can easily incorporate sound and visuals, and readers can access an entire library from their phone or laptop. But even in a year (and future) dominated by digital, print books continue to hold their own.”

Alex Payne – Music:

“Not having ownership of our music may be the best thing that’s ever happened to us. As consumers, we now get to have our cake and eat it! Being forced to have our music in an exclusively tangible form came at a costly price: the depth of our music exploration was once hard capped by the amount of money that you were willing to stump up, and for all but the ultra-dedicated, was limited to what HMV decided to put on the shelves. For less than the price of a single on CD, we now have near unlimited access to all flavours of Western music, and we’ve retained the option to buy a physical copy if we so wish.

Without undermining genuine concerns over stingy pay, it’s clear that nascent musicians benefit tremendously from the existence of streaming. The costs of printing CDs, tapes and vinyl records hasn’t been removed – but it’s been made entirely optional. Gone is the financial barrier, and thus the reliance on controlling labels with capital, which has massively democratised the industry. Any wanna-be musician can now begin to build an audience cost-free, making that initial plunge into the industry far less of a risk, which can be best seen with the explosion of Soundcloud rap in the early 2010s. It seems healthier for the wider industry, too. For over two decades the music industry was plagued by piracy, which ate into potential revenue and harmed artists, labels and venues to such a level that it wasn’t until 2015 that the industry turned a profit. Streaming services undermine the need for piracy entirely, because we can now enjoy any album for no pecuniary cost, and still support those who created it. Now that the industry has adapted to it, making ownership optional has had a profoundly positive impact on the industry, small musicians, and consumers.”

The common denominator here is accessibility, both for artists, authors and filmmakers, and consumers alike; making producing and consuming media more accessible in relation to choice and accessibility. Streaming services are undoubtedly better value for consumers and allow creatives to breach into their respective industries; whether that be independent musicians on Soundcloud or self-published authors that can publish their work en masse online, the viability to get your work out on digital platforms are a prime example as to how all of these industries are shifting with a more aligned focus on industry and independent creatives. And consumers can get on in this too, accessibility is at the heart of digital distribution with huge choice at attainable prices for the masses. Perhaps as a result we must forgo traditional ownership in the name of convenience, accessibility and choiceÔǪ which doesn’t sound bad to me.

Instagram: @quenchdownload

Write for us: email – [email protected] or join the Facebook contributor group

Check out our other articles here